In the beginning of The Red Pony, there is a boy, Jody. He is ten years old. He has a few chores which he does haphazardly and thoughtlessly. He’s bored. He throws stones at birds, kicks musk-melons, and is really invested in nothing. He is curious but aimless. He possesses a 22. rifle, but he’s not old enough to have cartridges. Upon receiving the red pony from his father, he is given his first opportunity to take care of something, and now he must engage in meaningful work. For the first time in his life, he gets up before the ringing of the bell to head down to the barn. He begins to take pride in his labor, thinking of how he might do it better and better. He is in love with something living for the first time.

This is an important step for him. With age comes responsibility. As he takes care of his horse, readying it for saddling and riding, he begins to imagine himself into his future. It is thrilling, the surge of life force embodied in both the pony and the boy. He pays attention to the musculature and gleaming coat, the flickering ears, to the way he can help his pony prosper, alert to the life before him. As a small boy though, he is not yet ready or able to imagine a darker side to that future. He can not imagine the horse’s throat having to be cut, or the bloody phlegm, or that sickness and vultures that would carry his horse away. He can not know that inchoate rage and loss and grief will be a part of the gift. So the gift of the horse carries with it the totality of life force, and death. This is what Jody comes to see and begin to understand. It’s his first vision of the awesome dimensions of living. Though we are sure that his father did not give him this pony to teach him about loss and grief, what happens to the pony becomes a necessary part of Jody’s learning.

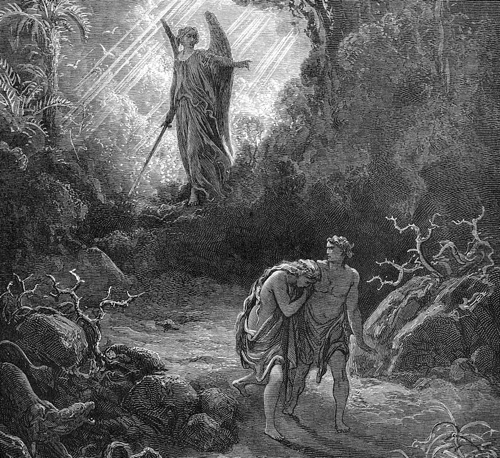

It’s a bit like Adam and Eve in the Garden. Before they are banished and sent east of Eden, they are in a suspended state of being where they know nothing of love or labor, accomplishment or loss, tension or growth. They are just “there” with no center around which to build their own lives. In Milton’s Paradise Lost, when they are sent from the garden, the last lines read:

They, looking back, all the eastern side beheld

Of Paradise, so late their happy seat,

Waved over by that flaming brand; the gate

With dreadful faces thronged, and fiery arms:

Some natural tears they dropt, but wiped them soon;

The world was all before them, where to choose

Their place of rest, and Providence their guide:

They, hand in hand, with wandering steps and slow,

Through Eden took their solitary way.

It’s important to note that once out of Eden, Adam and Eve now have each other. They hold hands, bonded in human love, leaning upon each other, with the world newly stretching out to infinity. There is terror and loss in it, of moving from one state of being to another, bound up in a mistake or misstep. But it’s also an image of regeneration, of the immensity of new beginnings, alive with the possibility of choice and will and creation. There are tears, yes, but they are wiped soon, and the world lays all before them, and they now must make their way.

In the very first chapter, the horse, so late Jody’s happy seat, is lost. So he is initiated into the blood and marrow of life. Seeing the vultures peck at his dead pony’s eyes, he thinks he could kill death. He can’t, because death must come, somehow, some way. He’s touched and has been touched by the fire and passion of life and death, and so awakens into the greater dimensions of his own existence.

To read the first chapter is to feel heartbreak. It is also true that our students, with their expanding minds and fast blooming consciousness, are becoming aware of so much at this stage of their lives. They are seeing more, understanding more, changing more. Their brains are becoming ever more complex, with the ability to think about their feelings, see themselves from outside their own bodies, to think and wonder about what others may be thinking or feeling. The amount of new thought and understanding is staggering and sometimes overwhelming, the speed with which change overcomes them dizzying. Among other new horizons, kids the age of those at North Branch School are recognizing in a conscious way their place in the world, that they have the power and responsibility to begin to think about their place in the world. They get to, and must, chose how they will make their place, how they will “dare to disturb the universe.” They feel and begin to comprehend the tensions and struggles of the adults around them. They go from seeing things in concrete and literal terms to being able to see abstractly, figuratively, meta-cognitively. They begin to sense the size of the world, the depth of feeling, the immensity of what there is to learn, the nature of human love and compassion, and the sometimes scary abyss of what they do not yet know.

This tension, these new forces buffeting them, these tectonic shifts and rough dislocations are why there is so much emotion and energy in them, why suddenly out of stillness or stagnation there is eruption and shifting. These places of tension, as with Jody and his pony, are where the most learning happens.

***

I mentioned the Richard Wilbur’s poem, “The Writer” at our parent meeting the other night. For me, as a teacher and parent, as someone who has spent 30-plus years watching and learning from adolescents, this poem captures the essence of what is happening to kids this age.

As rites of passage from cultures all over the world remind us, adolescence is a time of crossing over. From childhood to adulthood, from “Eden” into the world, from living in a world that has been made to having the power to make the world; from being held to learning how to hold; from the bliss of innocence to a beginning comprehension of the grit and beauty of experience.

In her room at the prow of the house

Where light breaks, and the windows are tossed with linden,

My daughter is writing a story.

I pause in the stairwell, hearing

From her shut door a commotion of typewriter-keys

Like a chain hauled over a gunwale.

Young as she is, the stuff

Of her life is a great cargo, and some of it heavy:

I wish her a lucky passage.

But now it is she who pauses,

As if to reject my thought and its easy figure.

A stillness greatens, in which

The whole house seems to be thinking,

And then she is at it again with a bunched clamor

Of strokes, and again is silent.

I remember the dazed starling

Which was trapped in that very room, two years ago;

How we stole in, lifted a sash

And retreated, not to affright it;

And how for a helpless hour, through the crack of the door,

We watched the sleek, wild, dark

And iridescent creature

Batter against the brilliance, drop like a glove

To the hard floor, or the desk-top,

And wait then, humped and bloody,

For the wits to try it again; and how our spirits

Rose when, suddenly sure,

It lifted off from a chair-back,

Beating a smooth course for the right window

And clearing the sill of the world.

It is always a matter, my darling,

Of life or death, as I had forgotten. I wish

What I wished you before, but harder.

This poem marks that time and place where a child finds herself ready to chart her “smooth course for the right window” of her life. She wants to write, to imagine herself, to begin making a story. The father offers up a simple metaphor early in the poem: The stuff of her life is “great cargo, and I wish her a lucky passage.” It’s too easy though. He’s left out the hard part. He later realizes that this is an “easy figure,” a simple, depthless way to have thought about it. He realizes this after remembering the starling that was strapped in the room, that battered its head against the wall, kept trying, kept regathering its wits to try again. Remembering this, the father understands that the pain, the stumbling starts and restarts, the gathering of wits, the repeated struggles–all of this is necessary for her find herself and to author her own story. As difficult as it is, there are times where he must stand back, close by but back, to listen, trust, hope, observe, wait, and know that she will find her way.

It is a tenuous place to be. I suppose it’s a time of “holding on loosely” as the terrible song by .38 Special once reminded us. We want to have our hands on them, be guiding them, directing them, not letting them fall or fail. But there are times when they do need to be alone to struggle and find their way, to know what tension is and how to navigate their way through it. In the struggle and the repeated attempts is where the most learning and growth happens. They are learning that they must shape the world with as much care as Jody tended to his pony. That’s where they really begin to see themselves finding and making a way that is their own.